Photographs by Elinor Carucci

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. somehow knew, even as a little boy, that fate can lead a person to terrible places. “I always had the feeling that we were all involved in some great crusade,” Kennedy once wrote, “that the world was a battleground for good and evil, and that our lives would be consumed in that conflict.” He was 9 years old when his uncle was assassinated and 14 when his father suffered the same fate. I happened to be sitting next to him this fall when he learned that his friend Charlie Kirk had been shot. We were on an Air National Guard C-40C Clipper en route from Chicago to Washington, D.C., and one of Kennedy’s advisers, her eyes filling with tears, whispered the news in his ear. “Oh my God,” he said.

National Guard stewards handed out reheated chicken quesadillas, which Kennedy declined in favor of the quart of plain, organic, grass-fed yogurt his body man had secured for him. A few weeks earlier, a man who believed that he’d been poisoned by a COVID vaccine had fired nearly 200 bullets at the CDC’s campus in Atlanta, hitting six buildings and killing a police officer. Kennedy, who as secretary of Health and Human Services oversees the CDC, had just told me that his security team recently circulated a memo warning him of threats to his own life. “It said the resentments against me had elevated ‘above the threshold of lethality,’ ” he said. Kennedy greeted the threat assessment with remarkable equanimity. He put down his spoon in order to finish his yogurt in gulps directly from the container.

In an atmosphere of rising distrust of U.S. institutions, where even once-untouchable bastions of expertise such as the scientific establishment had been badly weakened by the coronavirus pandemic, Kennedy had emerged as a Rorschach test—truth-telling crusader, or brain-wormed loon?—for how Americans understood the populist furies riling the country. I’d told him that I wanted to understand his journey from liberal Democrat and environmental activist to MAGA insider and Kennedy-family heretic, on the theory that by examining his odyssey, I might better understand what separates us and help narrow the political divide. He was sympathetic but skeptical. “Yeah, if you pull that off …,” he said, trailing off with a laugh.

Kennedy himself has done much to fuel the rising distrust. He views some of the world’s most celebrated scientific and political leaders as charlatans. He calls some of the experts who work under him at HHS “biostitutes,” because he considers their integrity for sale to the industries they regulate. He rejects much of the scientific consensus regarding vaccines, arguing that they have likely seeded the growing epidemic of chronic illnesses. During a Senate Finance Committee hearing just days before our flight from Chicago, Kennedy had called one U.S. senator a liar and another ridiculous. A bipartisan majority of the panel, including two Republican doctors, voiced concerns that vaccine policies he supported threatened the lives of American children. Kennedy argues that journalists like me are complicit, along with the public-health establishment, in hiding truth from the American people. The nation was tearing itself apart, and Kennedy had positioned himself at the seams.

“The whole medical establishment has huge stakes and equities that I’m now threatening,” he told me. “And I’m shocked President Trump lets me do it.”

A year earlier, Kirk, the founder of the conservative youth group Turning Point USA, had hosted an event with Kennedy the same day the candidate ended his quixotic presidential campaign and endorsed Donald Trump. JFK and RFK Sr. “are looking down right now and they are very, very proud,” Trump had said on the occasion. Now, as we flew over Ohio, no one knew if Kirk would live. At the front of the plane, aides to Attorney General Pam Bondi, who was also on board, were using the in-flight Wi-Fi to stream the gruesome videos of the shooting on social media. Kennedy’s adviser came back with a draft post for the secretary’s X account: “Praying for you, Charlie.”

“Say ‘We love you, Charlie.’ ” Kennedy instructed.

Three days later, Kennedy had just returned from a Saturday-morning 12-step meeting for addiction near his new house in Georgetown—a neighborhood that the extended Kennedy clan had long called home but that he now described as a “liberal enclave”—when he texted me saying that he wanted to continue our conversation about the country’s social breakdown.

A majority of the people in his recovery meeting, he said, “were probably horrified the first time I walked in, because, you know, they read The New York Times and they watch CNN, and so I’m kind of like a monster to them,” he said. “Over time, I became very welcome.”

This gave him hope that, outside the rooms of recovery, we could shrink our divisions. Parts of society, he said, are supposed to function independent of politics. Science is one of them. “The entire purpose of science is to search for existential truths,” he said. “It’s not subjective. It should be objective. I believe science is a place where you can find unity if you can get a conversation going.”

The problem is that the conversation had long since broken down. In 1900, the top three causes of death in the United States were pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diarrheal diseases, which collectively killed nearly 1 percent of the country every year. A staggering 30 percent of all deaths occurred in children younger than 5. By the end of the century, vaccinations, antibiotics, clean water, improved sewage treatment, and pest control had drastically reduced the lethality of infectious diseases. Today, young children account for less than 1 percent of U.S. deaths. Life expectancy has been extended by nearly 30 years. This is a monumental accomplishment, attributable to the efforts of scientists and lawmakers who tested hypotheses, built consensus to pass policies, and then corrected that consensus when new evidence arose.

But since about 2010, the long, steady increase in life expectancy has flatlined. Chronic illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and lung disease now top our mortality tables—affecting some 130 million Americans and accounting for 90 percent of our $4.9 trillion annual health-care expenditure. We are the world’s least healthy high-income nation, bombarded with prescription-drug ads and buffeted by a wellness industry of alternative fixes. A September poll by Navigator, a Democratic public-opinion firm, found that seven in 10 Americans are convinced that the health system “is designed so drug and insurance companies make more money when Americans are sick.”

Kennedy aims to channel the frustrations of that majority to remake public health. He arrived at this goal by way of his decades as a trial lawyer focused on contamination of the nation’s water by polluting corporations. In the latter part of his career, he has come to perceive a comparable contamination of American health by pharmaceutical and food companies. A central premise of Kennedy’s leadership at HHS is that modern science is infected with bias that costs lives—that the regulatory agencies have been captured by industry, that medical journals are corrupted by the need to turn a profit, that even respected organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics operate with a myopic groupthink that hurts kids.

For years, Kennedy was a gadfly outsider. The scientific establishment ignored him. Even now that he sits atop America’s health bureaucracy, Kennedy told me, public-health authorities—whose convictions, he said, are more akin to religion than science—will not engage with him. He blamed his opponents for dodging his arguments on vaccines. “Why for 15 years have they refused to have a conversation with me? I’ve been asking for 15 years for somebody to come up and debate me on this,” he told me. “Their reaction to that is ‘Oh, don’t debate him. He’s too crazy. You don’t want to give him a platform.’ ”

In 2017, Kennedy thought he’d finally gotten the audience that would allow him to make his case about vaccines. At Trump’s insistence, Kennedy and some allies, including Aaron Siri, a vaccine-safety litigator, came to the National Institutes of Health with a stack of 84 studies that they said supported their claims about the unrecognized dangers of vaccines.

“We tried to engage him. We were trying to debate him,” Joshua Gordon, the former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, told me. He and his colleagues attended the meeting to argue that existing studies demonstrated no connection between vaccines and conditions such as autism, and to explain why Kennedy’s papers “were suspect.” But, Gordon said, “Kennedy and Siri refused to engage.”

Kennedy and Siri insist that it was the doctors and scientists who refused to engage, and Siri has published emails showing that Gordon eventually ended the conversation by referring them to the CDC. The meeting solidified Kennedy’s conviction that he was dealing with a cult unwilling to look at evidence that challenged its worldview.

Today, a similar pattern is playing out between Kennedy and his own staff. In late August, Kennedy asked that Trump fire Kennedy’s handpicked CDC director, just four weeks after she’d been confirmed by the Senate, because Kennedy was convinced that she was aligning herself with her agency’s scientific staff and against him. He replaced the members of the CDC’s vaccine advisory committee because he’d concluded that their COVID-era decision making had been unscientific and industry-influenced. His team uses social media to attack science reporters by name.

Even some members of Kennedy’s newly adopted party are alarmed. Last February, Senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a gastroenterologist and the Republican chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, cast the deciding vote to confirm Kennedy as HHS secretary. A liver specialist, Cassidy has treated patients with cirrhosis caused by having been born with hepatitis B, a condition that can be avoided with newborn vaccination. Though Cassidy has thus far declined to renounce his endorsement of Kennedy, he rejects the secretary’s suggestion that the hepatitis vaccine might be dangerous when given to newborns.

“I’ve invited Bill Cassidy and others to sit down with me and go through the studies and let’s figure out which ones are right,” Kennedy told me. “That has to happen through real debate and conversation, and there’s no real place to have that in the current political milieu.”

When I conveyed Kennedy’s frustrations to Cassidy, the senator said that he and the HHS secretary regularly share scientific articles and papers with each other. “I find that he often will send me the same article more than once,” Cassidy told me. Yet whenever Cassidy points out “statistical flaws” in the article, he said, Kennedy says he considers those “immaterial.”

I had been having a similar experience. As I reported this article, Kennedy referred me to many studies meant to convince me there are not two valid sides to this debate, that his is the only valid one. I’m not a scientist. I’ve admittedly been inconsistent in getting my yearly COVID and flu boosters, confused about their benefits. Now the most powerful public-health official in the U.S. was asking me, a political reporter, to referee a medical debate with life-and-death stakes.

I called Paul Offit, a pediatrician and the director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and one of the most outspoken critics of Kennedy’s vaccine views. Offit helped invent a rotavirus vaccine that has mitigated a major cause of early-childhood hospitalization around the world. Kennedy routinely attacks him as a paragon of financial conflict because the owners of the vaccine patent, including his hospital, gave him some of the proceeds from its sale. The accusation relies entirely on circumstantial evidence: Offit’s early rotavirus research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, not private industry; he advocates for vaccination and sells books about the benefits of vaccines, but nothing suggests that he has ever done anything untoward in pursuit of profit. Like many of the people I spoke with for this article, Offit has faced death threats from radicals who believe his vaccine advocacy is deadly. Some have targeted his children.

Offit told me that Kennedy is a “liar” and a “terrible human being.” I asked him to explain. “It doesn’t matter what I say,” Offit said. “He thinks the medical journals are in the pocket of the industry, he thinks that the government is in the pocket of the industry, he thinks I’m in the pocket of industry, and he’s wrong.” Offit continued: “If he has data showing he’s right, then fucking publish it. He can’t, because he doesn’t have those data.”

I asked Offit if he saw a way to reverse the public’s rising distrust in science. “I don’t think there is any way to regain that trust other than have the viruses do the education, and the bacteria do the education, and then people will realize they paid way too high a cost,” he said.

From 2011 to 2024, the percentage of kindergarten students whose families asked for nonmedical exemptions to vaccine mandates doubled, to more than 3 percent, according to the CDC. Florida just announced an end to school vaccine mandates, and Idaho passed a law banning them. Cassidy’s office has been monitoring rising rates of pertussis, a bacterial infection also known as whooping cough; symptomatic infection is avoidable with a vaccine. Cassidy’s working hypothesis is that declining vaccination rates in red states will show up in the data. Kennedy counters that existing data are not specific enough to show whether the new infections are among the unvaccinated.

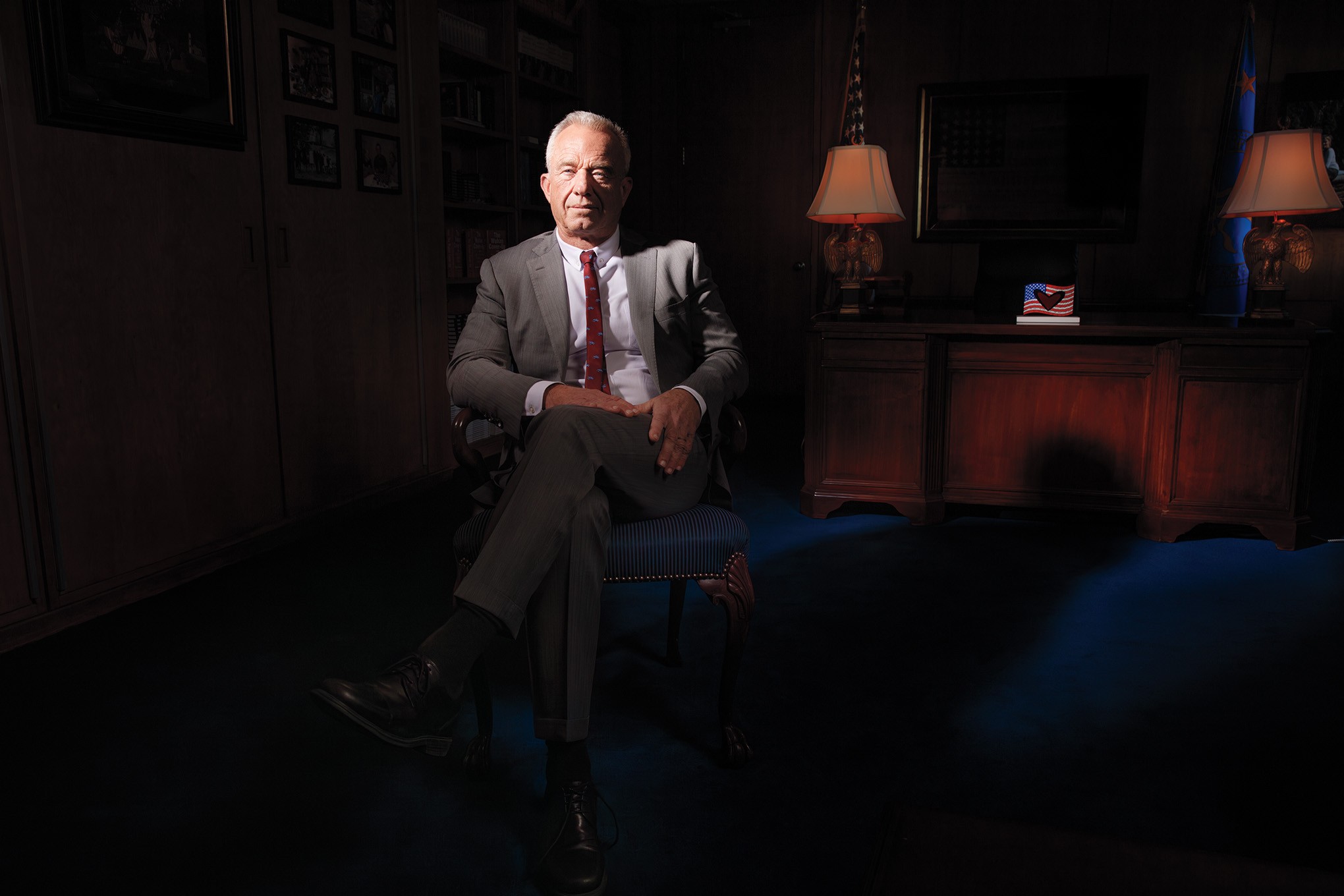

I first interviewed Kennedy for this story in June, in his office on the sixth floor of HHS headquarters, a brutalist gray block of concrete that resembles a giant air-conditioning unit. Kennedy’s staff jokes that the building feels like a prison; the secretary pointed out the great view he would have of the U.S. Capitol’s dome, if not for the building’s deep-set windows.

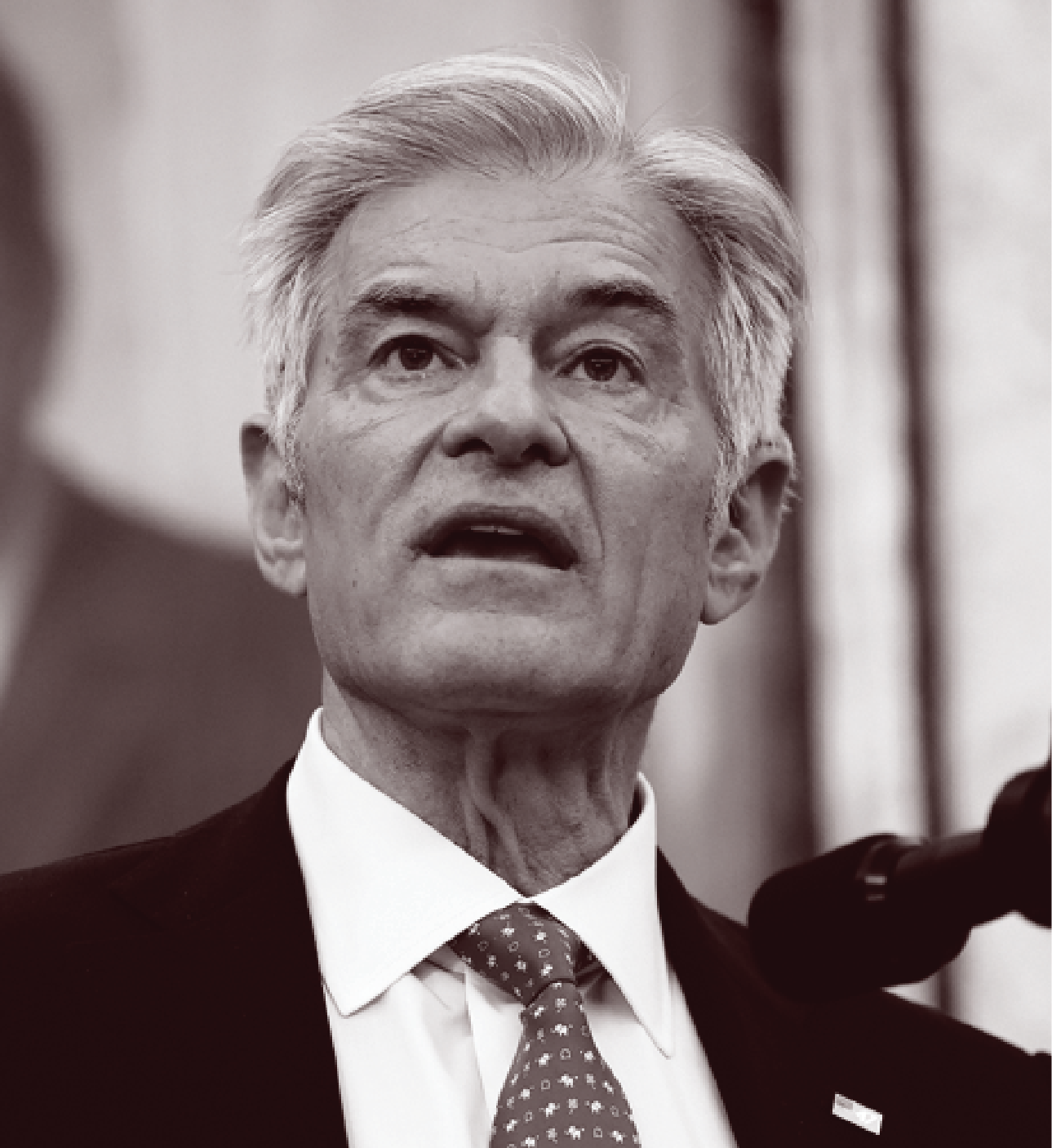

Kennedy is 71, but with the help of weight lifting, artificial tanning, a careful diet, and testosterone-replacement therapy, he looks more like a comic-book character than a senior citizen, his bronzed face all chiseled angles, his eyes sky blue. He adheres to a strict uniform at work—dark, embroidered skinny ties like his father sometimes wore, with suit jackets that bulge over his bodybuilder’s chest and biceps. He regularly pulls Zyn nicotine pouches from his shirt pocket or desk drawers to tuck between his lower lip and gum. When I asked him to square his nicotine habit and the time he spends tanning with the federal health advisories against both, he shifted in his chair. “I’m not telling people that they should do anything that I do,” he said. “I just say ‘Get in shape.’ ”

Kennedy told me his staff believed that speaking with me was a mistake. For the first half century of his life, national magazines hailed him as a public servant, a potential heir to the Kennedy kingdom—even, as Time magazine put it in 1999, a “Hero for the Planet.” “The Kennedy Who Matters,” New York magazine declared in 1995, saluting RFK Jr.’s environmental advocacy. In 2006, Vanity Fair posed him on the cover of its “green issue” with George Clooney and Julia Roberts.

But the favorable coverage dried up about 20 years ago, when he began arguing that mercury additives in vaccines were likely causing an epidemic of autism. This claim was contradicted even at the time by epidemiological studies by the CDC and others. Editors who did not want to discourage lifesaving vaccination stopped running flattering articles and started running critical ones. “All-out hit pieces,” he told me, “every one of them—like, ugly, hateful stuff.” For 20 years now, he said, only “bad articles” have been written about him.

Yet in the aftermath of COVID, his popularity has surged. Like Trump, Kennedy has drafted on the currents of populist backlash against expert authority. “When I’m on the street, I get stopped three times a block by people saying that they love me,” he said. Kennedy is among the most popular members of Trump’s Cabinet, according to an August Gallup survey: 42 percent of the country holds a favorable view of him, on par with the president himself. The public attacks on Kennedy’s character and integrity bother him, naturally, but he wanted me to know that I was not a threat. “If he screws us on this,” he recounted telling his staff, “it’s just another shitty article in a liberal paper, which doesn’t really hurt me.”

He believed that I’d screwed him before, anyway. I’d first met him in the spring of 2023, when he was challenging President Joe Biden for the Democratic Party’s nomination. The Washington Post story I wrote focused on his argument that the powerful were lying to the American people—about vaccines, environmental threats, the assassinations of his father and uncle, and much else. He hated the story largely because I’d used the word conspiratorial in the headline, which he argued was an elitist epithet for tinfoil hat. I placed him in the tradition of what the political scientist Richard Hofstadter described as America’s paranoid style, while acknowledging that secret conspiracies of the powerful—tobacco companies, the intelligence community—sometimes do exist.

He responded by sending me an email nearly twice the length of my original article, with 78 footnotes. (At the time, he was suing the Post for its role in a consortium designed to combat misinformation online.) “Your reporting on me reflects, exquisitely, the overt aspirations by your employer and its co-conspirators to crush nonconformist viewpoints in order to secure their own economic self-interests,” he wrote. Weeks later, on a podcast, he accused me of being “part of a conspiracy, a true conspiracy.”

I had never received an email like that from a politician. If I was hopelessly corrupt, why spend hours writing a response? It struck me that Kennedy believed himself to be on a ferocious quest. “There is nothing that is a show about what you are seeing,” Mike Papantonio, a former legal partner of Kennedy’s who co-hosted a program with him on the liberal radio network Air America in the mid-aughts, told me. “That is real rage.”

Kennedy and I stayed in touch. In October 2023, getting little traction from Democratic-primary voters, he relaunched his presidential campaign as an independent. Despite not having a clear path to even a single electoral vote, he didn’t stop until August 2024, when he endorsed Trump, a man he had weeks earlier publicly described as appealing to “some of the darkest impulses in the national psyche.”

As we talked more recently in his wood-paneled HHS office, he leaned back in his chair behind an oversize desk, with one of his five book-length attacks on the federal medical establishment, The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health, displayed nearby. From that seat, he oversees one out of every four dollars in the federal budget and regulates about 17 percent of the nation’s economy. How, I asked him, did he explain going from scorned activist to the boss of the public-health apparatus?

“I would say in one word: providential,” Kennedy said.

If I were to do this story right, Kennedy told me, I needed to talk with his top deputies: Jay Bhattacharya, the director of the NIH; Marty Makary, the commissioner of the FDA; and Mehmet Oz, the cardiothoracic surgeon turned TV doctor known for having hyped dubious “miracle” cures, who is now running the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. All three of these physicians, like Kennedy, say that they were transformed by the pandemic, which they thought public-health authorities had mishandled. They had dissented from government edicts regarding vaccine mandates and masking. Although they do not embrace all of Kennedy’s views on vaccines, his deputies share his big-picture view that America’s public-health system is broken.

Early in the pandemic, Bhattacharya, a Stanford University physician and health economist, co-wrote the 2020 “Great Barrington Declaration,” a document that argued against universal COVID lockdowns in favor of allowing healthy people to gather while isolating only those groups at greatest risk of severe illness or death, such as the elderly and the infirm. For this, Bhattacharya was ostracized by colleagues at Stanford and the broader scientific community: An email that later became public shows Francis Collins, then the NIH director, telling colleagues that they needed a “quick and devastating published take down” of the declaration. (Tens of thousands of Americans a month were dying from COVID at that time; overstrained hospitals were at risk of collapse.) Death threats—a recurring feature of public-health work these days—followed for Bhattacharya, who now compares the COVID years to pre-Enlightenment Europe, when Galileo Galilei was imprisoned by Catholic leaders for arguing that the Earth orbited the sun.

“What you had is a relatively small number of scientists who could decide what is true or false for all of science and all of society,” Bhattacharya told me. Today, even some of those who led the public-health response during those years admit that COVID-vaccine mandates may have been counterproductive, that social distancing lasted too long, and that masking may not have done much to limit transmission—though it is also true that we cannot know now how much higher the death rate would have been without those measures in place.

The COVID vaccines led to a substantial reduction in hospitalization and death from the disease, according to peer-reviewed studies. But Kennedy likes to emphasize that, as the virus evolved, the vaccines failed to prevent infection, as scientific authorities had initially suggested they would. Kennedy also dismisses the mathematical modeling of the lives saved, and says CDC estimates of the COVID death toll were inflated by “data chaos” in the government. What no one doubts is that the severity of the pandemic—more than 95,000 Americans were reported dead in one month at its height—has transformed the nation’s relationship with medical authority. From 2020 to 2022, public confidence in the CDC dropped from 82 to 56 percent, according to a study by researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The country has still not recovered.

Kennedy’s team blames its Biden-era government predecessors. When I met with Makary, who worked as a pancreatic surgeon before being named FDA commissioner, he said that, in times of uncertainty, a dangerous and self-defeating “groupthink” can take over. Kennedy and his allies point to how public-health authorities urged social-media platforms to curb the posting of COVID misinformation, stifling debate. Kennedy himself got kicked off Instagram. In one social-media post, he called the death of the baseball great Hank Aaron at age 86 “part of a wave of suspicious deaths among elderly closely following” COVID-vaccine shots. Critics accused Kennedy of speculating baselessly about Aaron’s cause of death, and quoted the medical examiner’s office saying Aaron had died of natural causes. Kennedy, in turn, accused his critics of ruling out a vaccine connection without a proper autopsy, and demanded that one be done.

The COVID experience bonded Kennedy, Makary, Bhattacharya, and Oz in a fellowship of the ostracized. “We became renegades, personae non gratae, because we asked questions which you would think, certainly within academic medicine, you should be able to ask,” Oz told me in his office, where he keeps a taxidermic honey badger to symbolize fearlessness and aggression.

After Trump’s reelection, Kennedy’s HHS-leadership-team-in-waiting gathered at Oz’s 10-bedroom, 18,559-square-foot Palm Beach house, not far from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate. The house was built by the same architect who built the mansion down the beach where Kennedy had spent vacations during his childhood. “It has the same smell to it,” he said. In the mornings, Kennedy would call on anyone who was around to go swimming in the ocean or throw a football with him, before his team settled down to plan the future of U.S. medicine. Kennedy’s friend Russell Brand—a comedian, an actor, and a fellow recovering addict who has pleaded not guilty to rape and sexual-assault charges in England—would sometimes join them. Kennedy says that those months in Palm Beach validated his decision to walk further away from the Democratic Party and most of his own family, who remained prominent Trump opponents. The Republicans hanging around Oz’s house, Kennedy told me, “were all very idealistic people, which was not my view of the Republican Party growing up. To me the most breathtaking and refreshing part of being down there is that people were not sitting in rooms, as the Democrats imagine, thinking, How do we cut taxes for rich people and screw the poor? They were saying, ‘How do you make every American better?’ ”

At one point, leaders of Stanford visited, only to be grilled by Kennedy and Oz about why the university had opened an investigation into Bhattacharya’s professional conduct during the pandemic. The outcasts had become the authorities.

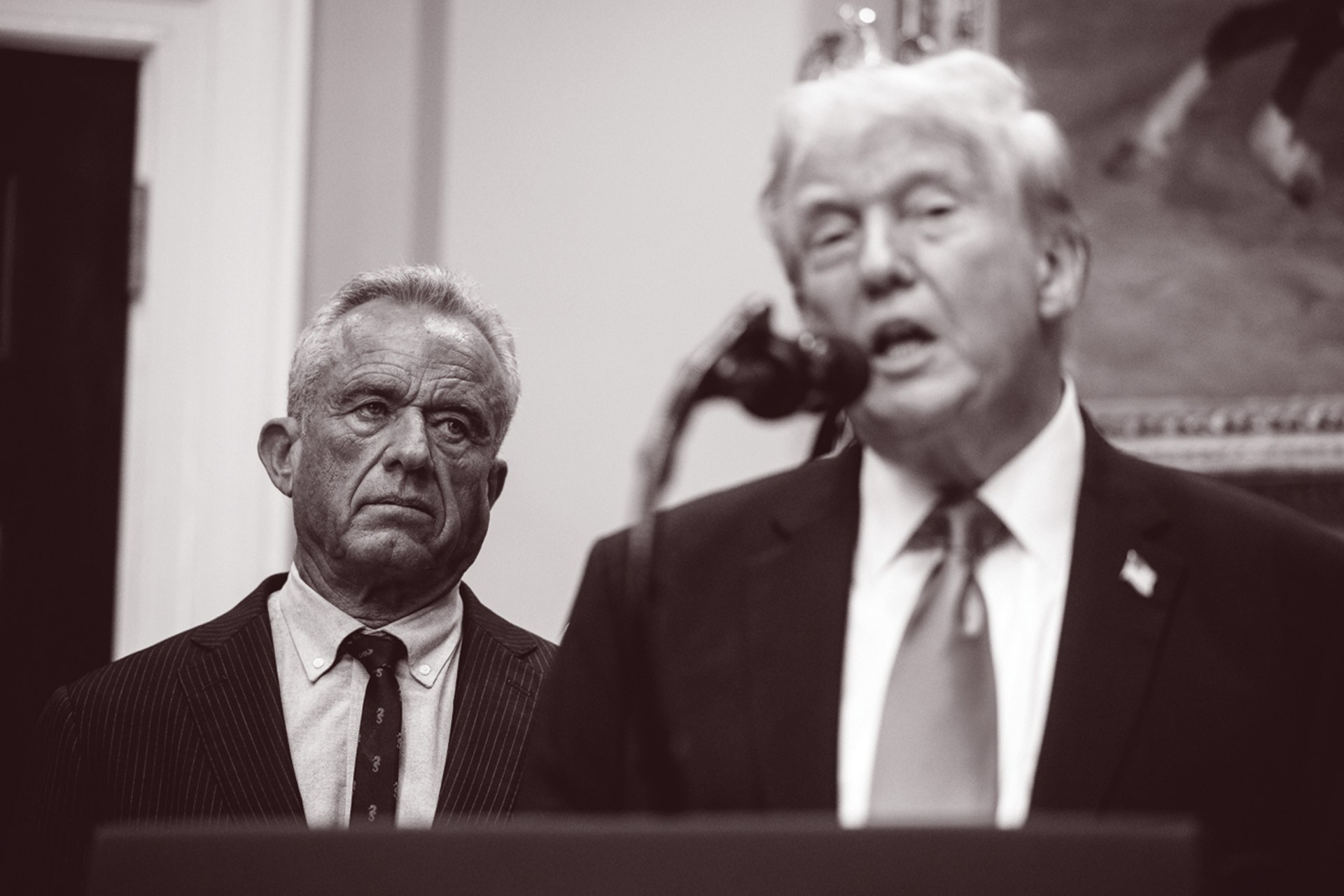

Kennedy now compares his relationship with the president to “when you’re dating somebody that you keep liking more and more.” They began meeting after the failed assassination attempt on Trump in July 2024. Kennedy came to believe that his previous impressions of Trump—that he was a “bombastic narcissist” who lacked curiosity and didn’t read books—had been wrong. “One day he sat on the plane with me. We were talking about Syria, and he drew a map of the Mideast for me. And it was a perfect map,” Kennedy told me. “Then he drew in the troop strength of each country, and also the troop strength on various borders.” Trump would recite sports trivia to Kennedy, and recount the net worth of major Wall Street financiers.

“I had to start seeing Trump as a populist who is standing up to really entrenched power and the deep state and that merger of state and corporate power,” Kennedy told me. He acknowledges that this makes Trump a strange “paradox”—“because he’s the most business-friendly guy at least since George W. Bush.”

That’s saying something coming from Kennedy, who in the early 2000s compared Bush’s pro-corporate environmental policies to the work of European fascists. I asked how he reconciled his criticism of Bush with working in the Cabinet of a president who appointed an oil executive, Chris Wright—who recently called Al Gore’s climate-change warnings “nonsense”—as energy secretary. “Chris Wright has a diverse worldview,” Kennedy told me.

For decades, RFK Jr. continued to call himself an “FDR/Kennedy liberal.” The embrace of MAGA has lost Kennedy friends and strained his family. At a rally against vaccine mandates in 2022, Kennedy described the U.S. COVID response as totalitarian, and warned that new technologies would give the government greater power to control Americans than the Nazis had over Anne Frank in Europe. In response, his sister Kerry Kennedy posted on X, “Bobby’s lies and fear-mongering yesterday were both sickening and destructive.” When RFK Jr.’s own wife, Cheryl Hines, famous for playing Larry David’s wife on the HBO show Curb Your Enthusiasm, publicly criticized him for those remarks, he apologized. Kennedy and Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democratic senator from Rhode Island, were once such close friends that they were in each other’s weddings. Now, when Whitehouse questions Kennedy at public hearings, his voice drips with disdain. “You have my cellphone,” Kennedy told his former friend during their last Finance Committee confrontation, in September. “I’ve never heard from you in seven months. Call me up. I’d love to meet with you.” (Kennedy says Whitehouse replied to his offer in late October and said he would meet, after Whitehouse’s Senate office had declined a request for comment from The Atlantic.) More recently, his cousin Tatiana Schlossberg, one of JFK’s granddaughters, who has terminal cancer, wrote in The New Yorker that she “watched from my hospital bed as Bobby, in the face of logic and common sense,” became HHS secretary, and admonished him for cutting cancer-research funding. (Kennedy declined to comment.)

“To stay on course despite that jeering really tells you a lot about his messianic self-regard,” the New York Democratic politician Mark Green, another former friend of Kennedy’s, told me recently. “He is sadly off his rocker to argue that Biden was more anti-speech and fascist than Donald Trump.”

Over time, Kennedy and his team united around an organizing theory of their department. “It’s a $1.73 trillion bundle of perverse incentives,” he told me. “The doctors, the hospitals, the insurance companies, the other providers, the pharmaceutical companies are all incentivized to make money by keeping people sick.” Fixing this would require radical measures.

The ensuing year has been a whirlwind of controversy, destruction, and new initiatives. Kennedy and the Trump White House pushed out, through firings and induced retirements, about one in four HHS employees, including much of the senior career staff and thousands of workers at the CDC, which Kennedy described to me as a “snake pit.” Early on, working with Elon Musk’s team at the Department of Government Efficiency, Kennedy canceled hundreds of millions of dollars in research grants, and defended a White House budget proposal that cut 40 percent of the NIH’s funding, even while saying that he would accept more money if Congress decided differently. “I talked to Elon a lot about this,” Kennedy told me. “You have to do something disruptive at the beginning.” If you don’t, “you lose momentum.”

On May 27, he shook scientists at the CDC by announcing that his department would no longer recommend COVID boosters for healthy children or pregnant women, on the grounds that clinical trials had not sufficiently demonstrated safety and efficacy for those populations. The career staff was outraged; Kennedy presented no new data on potential harm that would have compelled rescinding the existing recommendation, and it is well established that COVID infection increases the danger to both mother and fetus. “I knew that those decisions were going to harm people,” Lakshmi Panagiotakopoulos, a top adviser on COVID vaccines for the CDC, who resigned in response to Kennedy’s new policy, told me. “From my perspective as a scientist and someone who has done this her entire career, he has a lot of blood on his hands.”

Days later, Kennedy removed the 17 members of the CDC committee responsible for recommending vaccination schedules and replaced them with a smaller group that promptly ordered the removal of a mercury preservative, thimerosal, from flu vaccines, even though the CDC continues to describe thimerosal as “very safe.” Kennedy’s new committee put up barriers against a single shot to vaccinate children for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella, citing past studies by Merck and the CDC that found a higher incidence of febrile seizures following the combined vaccine. Kennedy also canceled $500 million in federal grants for mRNA-vaccine research, citing his conclusions, disputed by medical associations, that the technology performs poorly against fast-mutating respiratory viruses.

In other areas, he’s pushed for changes that health activists and wellness influencers on the left, as well as many in the scientific mainstream, have long sought. He launched initiatives to review baby-formula ingredients, issue new guidelines for fluoride use, limit student cellphone use, stop the sale of illegal flavored vapes, and remove restrictions on whole-milk sales at schools, and he persuaded governors in 12 states to ban the use of food stamps to buy sugary sodas. He announced plans to explore limits on direct pharmaceutical advertising and the marketing of unhealthy food to children, increase nutrition education for doctors, reduce prices on some drugs, add front-of-package labeling on ultra-processed foods, and require more testing of food additives. Under pressure from Kennedy’s HHS, major food producers announced that they would remove certain petroleum-based food dyes from cereals and candy.

Kennedy’s deputies describe him as endlessly curious about new science, and willing to listen to dissenting views. Bhattacharya told me that, during the 2025 measles outbreak in Texas, the worst in decades in the U.S., he privately advised Kennedy to endorse the measles vaccine as the most effective way to prevent the disease. “When you give him the evidence, he changes his mind along the lines of what the evidence says,” Bhattacharya said. Kennedy did go on to call the measles vaccine effective—while also emphasizing that parents should make their own decisions and promoting disputed treatments such as cod-liver oil for measles symptoms.

The secretary also consumes scientific studies by the bushel. In August, Andrea Baccarelli, the dean of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, published a review of the existing science suggesting a possible connection between taking Tylenol during pregnancy and the development of autism or attention deficit disorder in children. Kennedy told me he spent a weekend reading 70 studies related to this. He spoke with Baccarelli, started texting directly with another researcher on the topic, and asked the CEO of Kenvue, the company that now owns the Tylenol brand, to bring scientists to HHS to brief him.

Kennedy arrived at a rather nuanced set of conclusions—more nuanced than what his boss would subsequently express. High fevers in pregnant women are known to cause bad outcomes in newborns. So any public-health advice recommending against Tylenol, which reduces fevers, would have to be carefully weighed, he told me. But when he briefed Trump on his findings, Kennedy said, the president’s response was to suggest immediately posting a Tylenol warning on social media.

“You can’t do that,” Kennedy said he told the president. “There’s nuance to it, and you can’t scare people away from Tylenol, and you’re going to get a huge amount of pushback from powerful pharmaceutical companies.” Trump’s reply: “I don’t give a shit about that.” The FDA-advisory note that Marty Makary released to accompany the announcement weeks later asked doctors to exercise caution in using the medication for low-grade fevers but said that there was as yet no proof of a causal link between Tylenol and developmental disorders.

Trump, however, has less patience for nuance. “Don’t take Tylenol. Don’t take it,” the president said at a press conference on September 22. “Fight like hell not to take it.” The medical community responded with outrage. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and other prominent health organizations put out statements advising doctors and patients to disregard Trump’s recommendation.

Through all this, Kennedy has praised the president’s fearlessness and compassion. A few months earlier, at a White House event, RFK Jr. compared Trump to President Kennedy, who had worked with the biologist Rachel Carson in the early 1960s to reduce the use of pesticides. “My uncle tried to do this, but he was killed and it never got done,” Kennedy said, sitting alongside Trump. “And ever since then, we’ve been waiting for a president who would stand up and speak on behalf of the health of the American people.”

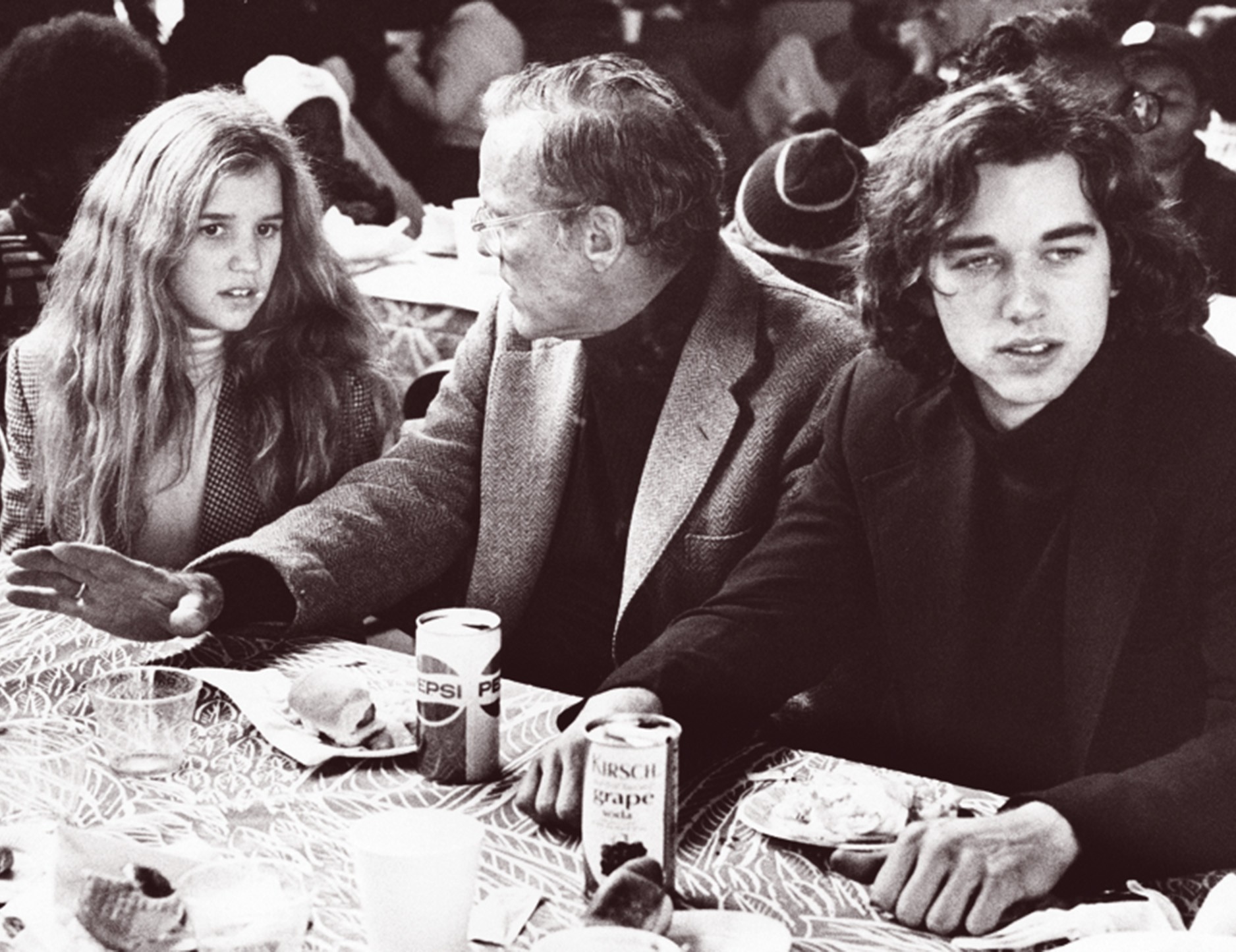

In a family steeped in its own mythology, RFK Jr. was always particularly susceptible to the pathos and grandeur of the Camelot mystique. His father encouraged him to read heroic poems like Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “Ulysses,” and as a child Bobby Jr. memorized Rudyard Kipling’s “If—” and “Gunga Din.”

The legend of King Arthur resonated with a boy who was more interested in catching salamanders and snakes in the forest than in schoolwork. T. H. White’s novel The Once and Future King, which tells the story of young Arthur’s tutelage under Merlyn, was a particular favorite. “That was how I got interested in falconry,” Kennedy told me. When he was 11, his father gave him his first red-tailed hawk. Kennedy named the bird Morgan le Fay, after Arthur’s sorcerer half sister.

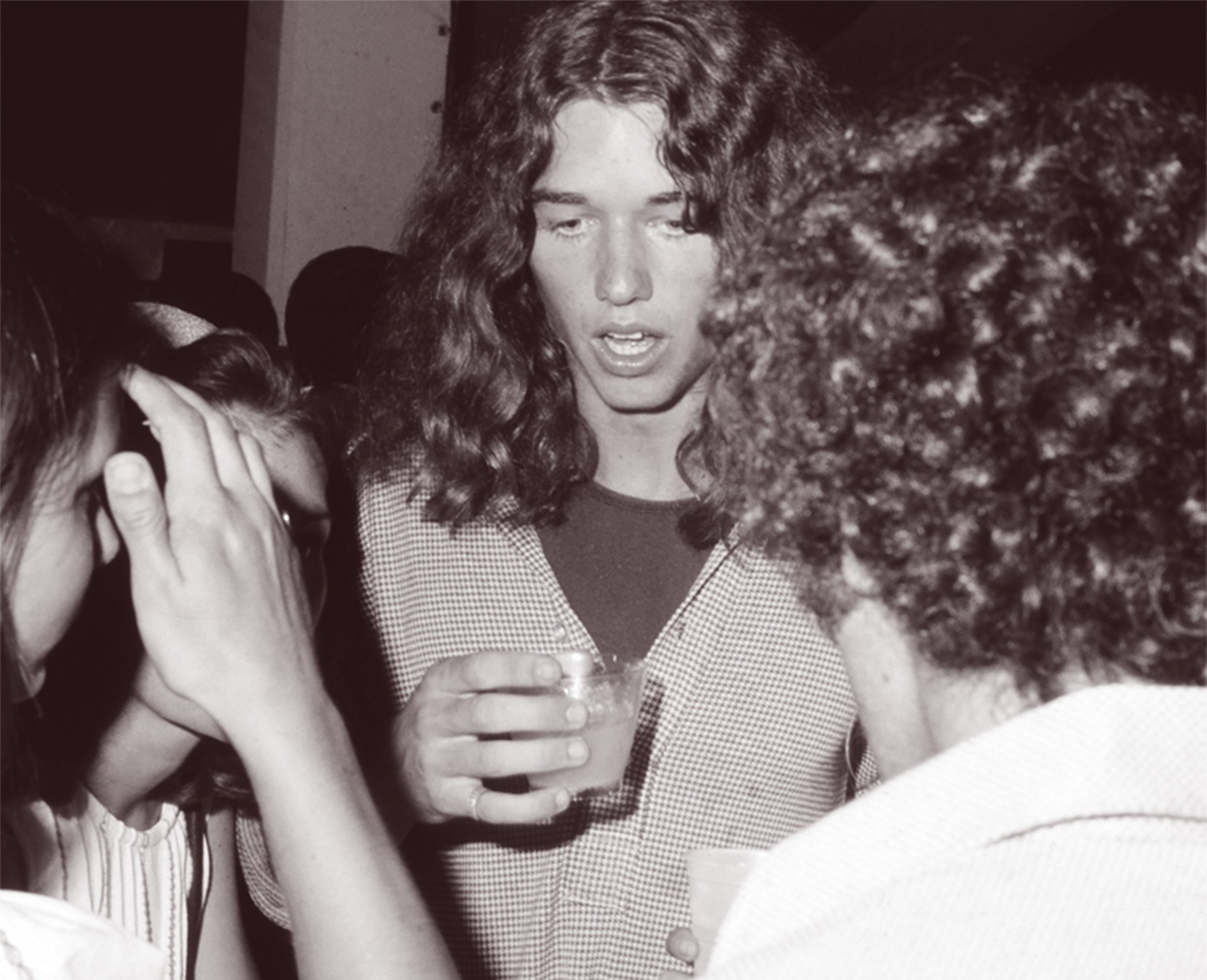

But when his father was murdered, Ethel Kennedy, Bobby Jr.’s mother, was left to care for 11 children in a world churning with youthful rebellion. One day in the summer of 1969, Kennedy remembers, he attended a farewell party on Cape Cod for a young soldier heading off to Vietnam. He said LSD had arrived from California that summer, and while he was hitchhiking home that night, someone offered him a dose. His favorite comic book at the time, Turok, Son of Stone, followed the exploits of Native Americans who lived among prehistoric animals. In one of the comic’s storylines, the Native Americans consume a hallucinogenic fruit. “Will I see dinosaurs?” Kennedy told me he asked the person offering him the LSD. “I had a deep interest in paleontology,” he explained to me. That was perhaps the first time this particular reason has ever been given for deciding to take psychedelics.

A picture of his dead father and uncle behind the counter of a local diner as the drug wore off spoiled his trip. At which point another group of kids offered him a line of crystal meth. The initial rush was strong enough to set him on a new life path. Within months, he was traveling to New York City to buy $2 heroin on 72nd Street. “I had been administering drugs and giving shots to animals since I was a kid. And so it wasn’t a hard jump for me,” he said, about using needles to inject himself with drugs. “There were other kids in my town who were shooting speed.” He was 15.

In January 2025, after Trump announced that he would be nominating Kennedy as HHS secretary, his cousin Caroline Kennedy, JFK’s daughter, wrote a public letter opposing his confirmation, in part because of what she’d witnessed during his years as a young drug user; she blamed him for leading others in the family “down the path of addiction.” She described young Bobby as a “predator” like the raptors he’d raised, saying he had grown “addicted to attention and power.” “His basement, his garage, and his dorm room were the centers of the action where drugs were available, and he enjoyed showing off how he put baby chickens and mice in the blender to feed his hawks,” she wrote. “It was often a perverse scene of despair and violence.”

When I read Kennedy those words, he barely reacted. “I would not contest it that much,” he said. “Addiction is kind of narcissistic.”

By the time he was accepted into Harvard (his father, his uncles, and his grandfather had all gone there), he had been pushed out of multiple boarding schools, been arrested for marijuana possession, and become estranged from his mother. When he was still a teenager, he hopped trains to Haight-Ashbury, in San Francisco, to hang with the hippies, and worked in a Colorado lumber camp. His heroin addiction would last 14 years, continuing during his time as a law student at the University of Virginia, as well as through his first marriage, to Emily Black, a fellow UVA law student, whom he married in 1982. In September 1983, he overdosed on a flight to South Dakota. He was charged with heroin possession, for which he was sentenced to two years’ probation, and spent the next five months in a rehab facility in New Jersey. Shortly after he left treatment, his brother David Kennedy, younger by about a year, died of a drug overdose in a Palm Beach hotel room while other family members were gathered at the Kennedy estate nearby.

Although Kennedy says he has not taken heroin since he got clean, he still considers his brain to be a sort of “formulation pharmacy,” able to transform anything—rock climbing, falconry, sex—into a drug. In 2024, New York magazine parted ways with its reporter Olivia Nuzzi after learning of what it deemed was an inappropriate personal relationship with Kennedy, whom she’d profiled the previous year. (After the print edition of this article went to press, more detailed allegations about his relationship with Nuzzi emerged. Kennedy declined to comment.) A former babysitter for Kennedy’s children told Vanity Fair that he had groped her when she was 23 and he was 45. Kennedy apologized to the babysitter in a text message after the article’s publication, though he said he did not remember the incidents she described. “I am not a church boy,” he said publicly. “I have so many skeletons in my closet that if they could all vote, I could run for king of the world.”

After his time in rehab in the early 1980s, Kennedy says he remade himself through the routines and principles of Alcoholics Anonymous—a combination of spiritual devotion, radical transparency, and a focus on service. As a presidential candidate, he told his security detail that he had to attend a 12-step meeting every day, no matter where he traveled. He has continued that practice since moving to Washington from Los Angeles. I asked him how much being an addict in recovery still affects him. “I think it’s shaped everything,” he said. Even as HHS secretary, he sponsors others in recovery. “I take calls all the time.”

In his own view, recovery from heroin addiction has returned him from damnation to walk again among the living. “Having kind of lived through hell,” he told me, paraphrasing something he said he’d read while he was still using, gives you a different perspective on life, and the opportunity for “a kind of redemption.” To rebuild his self-esteem, he worked to replace the secret shame of his addiction with a life dedicated to a purpose bigger than himself. In this way, his private recovery, anchored in his Catholic faith, fused with his public crusade against what he believes are grave threats to American health. But this is also, perhaps, what gives his jeremiads about vaccines and other matters such fervor. “You’ve got to, you know, completely commit yourself to a way of life,” he said, talking about the 12-step process. “It’s Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey that we are all on.”

After entering recovery, he built up Riverkeeper, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the Hudson River and other New York watersheds; founded an environmental-law practice; divorced Black; got married a second time, to Mary Richardson, an architect; and began a lifelong battle against chemical contamination of human health. In 2010, after 16 years of marriage, he filed for divorce from Richardson; she accused him of extensive infidelity, and he described her as abusive. Before the acrimonious proceedings concluded, Richardson committed suicide. In 2014, Kennedy married Hines. He has six children, two with Black and four with Richardson.

In his work as a litigator, he thrived: He won judgments against General Electric for contaminating the Hudson River; DuPont for contamination at a zinc-smelting plant in West Virginia; and Monsanto for a type of cancer allegedly caused by glyphosate, then the key ingredient of one of the world’s most popular herbicides, sold under the brand name Roundup. He argued many cases himself.

John Morgan, one of the nation’s most successful trial lawyers, worked with Kennedy on lawsuits after a natural-gas leak in Southern California in 2015 and the spectacular 2023 train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio. Morgan says there are three types of lawyers: finders, who get the plaintiffs; grinders, who try the cases; and minders, who keep it all on track. Kennedy was one of the best finders he’d ever met. “People follow him,” Morgan told me.

Although Kennedy has been litigating against environmental polluters for more than four decades, his focus on vaccines began only after mothers with autistic children started showing up at his talks—and after one of them persuaded him to read studies suggesting a link between vaccines and autism. The fact that vaccines can harm people is not contested: The existence of the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program is a testament to the American public-health establishment’s acknowledgment of that. The frequency and nature of that harm, however, is highly contested. From 2006 to 2022, about 5 billion vaccine doses were distributed in the U.S. The NVICP paid about one settlement for every 1 million doses. Kennedy believes that the real rate of injury could be 100 times higher than what is reported. As in his crusade against corporate polluters, he brings a litigator’s tools to the vaccine fight—humanizing the victims, demonizing his opponents, and overwhelming his audiences with his research and with the nuclear force of his indignation.

Science, unlike fairy tales and courtroom dramas, does not always offer a clear narrative. Initial results may fail to replicate. Real findings can get drowned out by statistical noise. Catastrophic side effects may take time to emerge. In the evolving search for truth, the public can find itself whipsawed: Margarine was a healthy butter alternative—until studies found it to be a source of the artificial trans fats that cause 50,000 premature deaths a year. The Merck drug Vioxx was a miracle pain reliever—until researchers estimated that it was associated with as many as 140,000 excess cases of heart disease. The food pyramid of the 1990s, which emphasized processed carbohydrates over fiber and protein, now looks like a sick joke given what research has shown about the roots of our current obesity epidemic.

Kennedy thinks more people should follow his lead by consuming science directly. “ ‘Trusting the experts’ is not a feature of science,” he likes to say. “It’s not a feature of democracy. It’s a feature of totalitarianism and religion.” But having everyone “do their own research,” as Kennedy recommends, was untenable even before the advent of technologies like nanoscience and genomic editing. When I suggested to Kennedy that he was now presuming to play the role of health expert himself, he rejected that. “I don’t tell people to trust me. I tell people, ‘Don’t trust me.’ ”

Throughout our conversations, we often found ourselves jousting about the details of one scientific debate or another. For instance, I reminded Kennedy that back in 2005, he had suggested that the removal of thimerosal from most vaccines would result in a decline in autism diagnoses—but that since then, thimerosal had been removed from most vaccines, yet autism diagnoses continued to rise. He in turn argued that this could be explained by the addition of aluminum to vaccines during that same period, and by the fact that some flu vaccines still contained thimerosal. But most pregnant women and young children no longer receive flu vaccines with the preservative—and that’s been true since before Kennedy banned thimerosal from flu vaccines.

Another time, he pointed out that the U.S., a heavily COVID-vaccinated country, represents only 4.2 percent of the global population but accounts for 19 percent of the deaths from COVID. I countered that those differences are likely explained by other factors, including America’s more comprehensive reporting, higher chronic-disease rates, older population, and colder climate. He conceded all of that, but said he was making a narrower point, which was that the notion “that the only thing that saved us was the vaccine is unconvincing.”

He sent me a placebo-controlled COVID-vaccine study of pregnant women, conducted by Pfizer, which showed more congenital anomalies in babies born to the vaccinated group than the unvaccinated group. I countered that Pfizer had found the difference statistically insignificant. The reason the difference didn’t reach statistical significance, he pushed back, was that the study was not large enough and “Pfizer cut it off as soon as they saw a bad result.” If true, this suggested malicious intent on the part of the company. “Why aren’t you asking Pfizer about this?” he asked. “You should be burning up their phone line.”

So I called Pfizer, which granted me an interview with a scientist who was part of the company’s COVID-vaccine program, but requested that I not use the scientist’s name, to protect their privacy. This researcher told me that the study had been stopped not because of a bad result but because the data revealed no safety concerns with the vaccine—which meant that keeping the control group from getting it would have been unethical, given the serious risks stemming from COVID infection during pregnancy.

The researcher also explained that further investigation had determined that, of all the congenital anomalies initially reported, only one had originated after the vaccine administration, at 24 weeks’ gestation. “You cannot make a vaccine responsible for something that happened before you gave the vaccine,” the researcher told me.

When presented with data that contradict his arguments, Kennedy regularly claims bad faith on the part of his adversaries—that they’re motivated by profit or professional advancement. His experience as a litigator may have made this reflexive. As John Morgan, his litigation partner, told me, it’s hard to sue polluters and cigarette companies and not come away convinced that the defendants are “in the business of premeditated murder.” Kennedy has applied the same lens to the medical establishment, casting it as powered by the big pharmaceutical companies and their government protectors—despite the fact that most pediatricians and virologists and epidemiologists have devoted their lives to helping children and reducing suffering.

And if Kennedy is so concerned about conflicts of interest, what of his overhauled CDC vaccine panel? Some of the experts he appointed had previously been paid to serve as witnesses for plaintiffs in vaccine-safety lawsuits. Kennedy himself, in addition to the millions he made as a trial lawyer, took a large salary from Children’s Health Defense—$510,515 in 2022—a nonprofit he led from 2016 to 2023 that fundraises to fight for tighter vaccine regulation. His entire political project—his campaign, his hiring by Trump, his role at HHS—is entwined with his ability to prove that scientists were deceiving the public about vaccines. He would lose a lot if he changed his mind.

During his presidential campaign, Kennedy would repeatedly say that in a study of the COVID vaccine, Pfizer had found that “the people who got the vaccine had a 23 percent higher death rate from all causes at the end of that study”; he still says this today. He bases this on his interpretation of an early trial of the Pfizer COVID vaccine, and it sounds terrifying—a smoking gun for those looking for a reason to doubt official health advice. The main takeaway from that 2020 trial was that the rate of infection was significantly lower in the vaccinated group than in the placebo group (eight infections versus 162). The study followed about 44,000 people, who were randomly divided into two blinded groups, one that got the COVID vaccine and one that got a placebo shot. Over the course of six months, 21 people in the vaccine group and 17 in the placebo group died. (Scientists use these numbers to derive what they call “all-cause mortality rates.”) These are the numbers Kennedy uses to claim that a study found that your risk of death increases by 23 percent if you take the vaccine.

But the scientists I spoke with about Kennedy’s assertion explained that the study was not large enough and did not last long enough to reveal any increased mortality risk. In addition, an FDA review said none of the deaths in the study was vaccine-related. (Kennedy says this review was subjective.) Kennedy’s numbers were also misleading. During the blinded portion of the study, there were 15 deaths in the vaccine group, and 14 deaths in the group that received the placebo. (After the unblinding, the placebo group started getting the vaccine.) In 2023, Peter Doshi, an editor of a prestigious British medical journal, wrote Kennedy’s team an email advising that, based on these numbers, the proper conclusion about mortality from the study was that “there were basically equal numbers of deaths in vaccine and placebo arms.”

As we talked and texted this past fall, Kennedy and I kept returning to the same arguments we’d been having two years earlier. He would point to the all-cause mortality data from the Pfizer-vaccine study. I would respond that scientists who understood the data said they didn’t mean what he said they did—and I would point out that, even after the virus had mutated into new variants, observational studies continued to show that the Pfizer shot remained highly effective against both hospitalization and death.

Kennedy refused to relent. When the vaccines were introduced, he told me, public-health experts “were telling people, ‘This will save your lives.’ They didn’t have evidence for that. Twenty-three percent all-cause mortality! That’s not meaningful? I don’t know what universe you’re living in.”

Vaccinologists told me they’re living in a universe where they are trained to read and interpret data—not one in which you cherry-pick data from studies, extrapolate alarmist conclusions, and then suggest that they show a vaccine-caused increase in mortality when in fact they show nothing of the sort.

Like Bhattacharya, Kennedy tends to invoke Galileo. But in Kennedy’s telling, the villains were not only the clergy who arrested Galileo and censured his discoveries, but also the astronomer’s fellow scientists, who, wary of suffering his fate, refused to look through his telescope. It is a parable that posits unrecognized vaccine dangers as a sort of fixed point in the night sky, a supernova or moon, ready for discovery by anyone willing to risk their reputation in order to seek the truth.

Four days after Charlie Kirk’s death, Kennedy asked to speak with me again. He had his daughter Kick set up a Zoom call so that he would have a recording of our exchange. My efforts to transcend the divide were not going well.

“You kind of telegraphed where you were going,” he said when we convened that Sunday. “That there’s two sides that aren’t hearing each other, and both of them are intractable, and both of them think they are science-based.” He called this a journalistic device. “It’s a little bit self-serving because, you know, the journalist takes the position that ‘Okay, I’m looking at this phenomenon where there’s two sides and I’m in the middle’—the wise person who can kind of see everything,” he said. He suggested that he regretted agreeing to talk with me, and compared our relationship to the fable of the scorpion who asks the frog for help crossing a river, only to sting and kill the frog after it does.

“Every article about me is the same, which is never science-based; it’s never an argument; it’s always an ad hominem attack,” he continued. “ ‘He’s a conspiracy theorist, he’s anti-science, he’s a crazy person, he’s got a brain worm,’ or the bear story, or the whale story, or the dog story, any of these, and that’s what they focus on.” Articles about some of these colorful episodes from his past, he believed, were efforts to distract from the substance of his arguments. “I challenge you to tell me one conspiracy that I’ve talked about that has not come true,” he said. “Is it a conspiracy that I said that glyphosate—that Roundup—can cause cancer, like non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma? All three juries agreed with me. Is it a conspiracy theory that I said that the COVID vaccine was not going to prevent transmission? Now everybody admits that. Is it a conspiracy theory that I said that masks are not science-based? Everybody now agrees with that. School closures were a mistake.”

He wasn’t done. He fumed that people had used his interest in his father’s and uncle’s assassinations to discredit him. “I’ve never said my father was killed by the CIA. I’ve said there’s circumstantial evidence.” No one, he said, has explained the inconsistencies in his father’s autopsy, which contradicted the claim that his father’s sole killer was the Palestinian activist Sirhan Sirhan. “Robert Kennedy was shot from behind four times. We know what happened to every bullet in Sirhan’s gun. He hit six other people. He could not have killed my father. So, you know, that’s a fact. It’s science. And maybe you can figure out a way that he could’ve gotten behind my father.”

We were back where we started. “You know, a real journalist” would report that people were afraid of his arguments and that they were denying facts, he said, “but I don’t think The Atlantic will allow you to do that.”

“You’re the HHS secretary,” I said. “Presumably you can call anybody at CDC to have this debate.”

“There’s 21,000 people in that agency, and I’m not going to have a personal debate with each one of them,” he responded. “By the way, they’re leaving because they can’t defend their position.” Of course, the people quitting their jobs would dispute that. But to win in the court of public opinion, I suspected, Kennedy preferred to debate me.

This was all starting to seem rather hopeless. As I drafted this article, I felt growing dismay over my inability to establish even the basic factual common ground that scientific progress generally requires. So I sent Kennedy a message describing where I had ended up, and asking for another conversation. Minutes later, an adviser texted: “Want to meet at Secretary’s house today at 1 pm?”

Kennedy bought his new Georgetown home, not far from where Uncle Jack had lived as a congressman and senator, weeks after his confirmation. An interior doorway is decorated with signed notes to him from four recent Republican presidents—Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Trump. I asked him why there were no letters from Barack Obama or Bill Clinton, the last presidents he’d campaigned for before Trump. “They’re in storage,” he said. An American flag from 1865 hangs in his living room, a companion, Kennedy told me, to one that was given to President Abraham Lincoln shortly before he was shot.

We started out by finding at least one point of agreement, the importance of free speech. In fact, Kennedy broke with many of his Republican brethren, saying that “anything that weaponizes Charlie Kirk’s death to justify censorship is not consistent with his values.”

Inevitably, though, we were soon back where we’d left off. Kennedy suggested that my story conclude by looking at a statement published on the CDC website—“Vaccines do not cause autism.” During the confirmation process, Bill Cassidy had made him promise not to remove the phrase in exchange for his vote. But Kennedy had a work-around. On November 19, he updated the page and put an asterisk next to the phrase, adding language stating that “studies have not ruled out the possibility that infant vaccines contribute to the development of autism.” Although the MMR vaccine and thimerosal have shown no ties to autism, Kennedy says he has not been able to find any studies of possible autism risk from various other childhood vaccines. This absence of research, he believes, undercuts the validity of the CDC website’s claim.

Kick joined us on the couch. Hines sat upstairs, running through the final edits of her memoir. I asked Kennedy: Was he now, as the nation’s health secretary, arguing that science showed vaccines caused autism, as he had in the past? Or was he simply arguing that the question had not been conclusively answered by science? He responded carefully. “I have opinions about things, but, you know, my opinions are irrelevant,” he said. “What we need is science, and we need definitive science. We have suggestive science.”

I had spoken with others about this point. They agreed with Kennedy that not every vaccine had been studied for its effect on autism rates. But they argued that doing so was not urgent, because the existing high-quality evidence around vaccines showed no connection. Joshua Gordon, who as the director of the National Institute of Mental Health helped oversee federal autism research, told me that the recent increase in autism rates could mostly be explained by broadened criteria for diagnosis and by the advancing average age of parents at the time of conception.

“If vaccines contribute to autism, it is such a very, very small effect that there is no question that if you did the study and you definitively showed the small effect, that small effect would be far outweighed by the benefit of vaccines,” Gordon told me. “The notion that after you did those studies you would come up with a different scientific recommendation is patently false.” When I asked him about the statement on the CDC website that Kennedy contests (“Vaccines do not cause autism”), Gordon said it was “a plain-English statement” that distilled the scientific consensus and was meant to encourage lifesaving vaccination.

Stanley Plotkin, one of the nation’s premier vaccinologists and the lead author of the medical-school textbook Plotkin’s Vaccines, had a similar message. “Can I say that vaccines do not cause autism?” he asked rhetorically. “All I can say is there is no evidence” that they do. He rejected some of the studies Kennedy cited as poorly conceived. He said he would not oppose a large new epidemiological study that looked at the issue, with the right design to take into account confounding variables. But he said he would not accept “a study constructed by a biased person with the objective of obtaining a certain result.”

Trump was duly elected, and he appointed Kennedy as HHS secretary to carry out priorities Trump had advanced during the campaign. This gives Kennedy’s scientific policies democratic legitimacy, even if trained health experts shudder at what that may mean. But as we sat in his living room, I realized that Kennedy was making an argument I had not previously understood—a policy claim, not a factual one. He was saying that regardless of the lives saved by vaccines, it was irresponsible for the government to recommend them without first comprehensively ruling out all hidden dangers. He believes that only a few vaccines, including the tuberculosis vaccine, have been studied enough to clear this bar. Kennedy had slashed the budget of his own department. But now, he says, he plans to spend billions of dollars on hundreds of studies investigating vaccines’ potential ties to chronic diseases. “The default setting in medicine is ‘Do no harm,’ ” he said, as we talked about the COVID-vaccine boosters. “You never do an intervention—particularly with a healthy human being—unless you know that it’s safe and effective. And we don’t know if it’s safe and effective.”

What if you are wrong about vaccines? I asked. Six former surgeons general, most vaccine experts, and almost the entire scientific establishment believes he is. What if, over time, the evidence shows that his actions lowered vaccination rates with no reduction in chronic diseases, but with an increase in suffering and death from viruses and bacteria? How would he respond?

“I mean, we would listen,” Kennedy said. It was the answer I wanted to hear. But then he listed, once again, the reasons he would not be wrong: He spoke about the chronic diseases that appear as potential adverse reactions on the manufacturers’ label for vaccines; the evidence that death rates from the diseases that vaccines inoculate against were already declining before the vaccines materialized; and America’s poor policy decisions and high mortality rates during the COVID years. “You know, we have all kinds of interventions,” he said. “Good health does not just come in a syringe.” The trial lawyer was still laboring to connect the dots that led to his preferred verdict, the orphaned child of American royalty, back from hell, still fighting to fulfill his birthright.

This article appears in the January 2026 print edition with the headline “The Most Powerful Man in Science.”